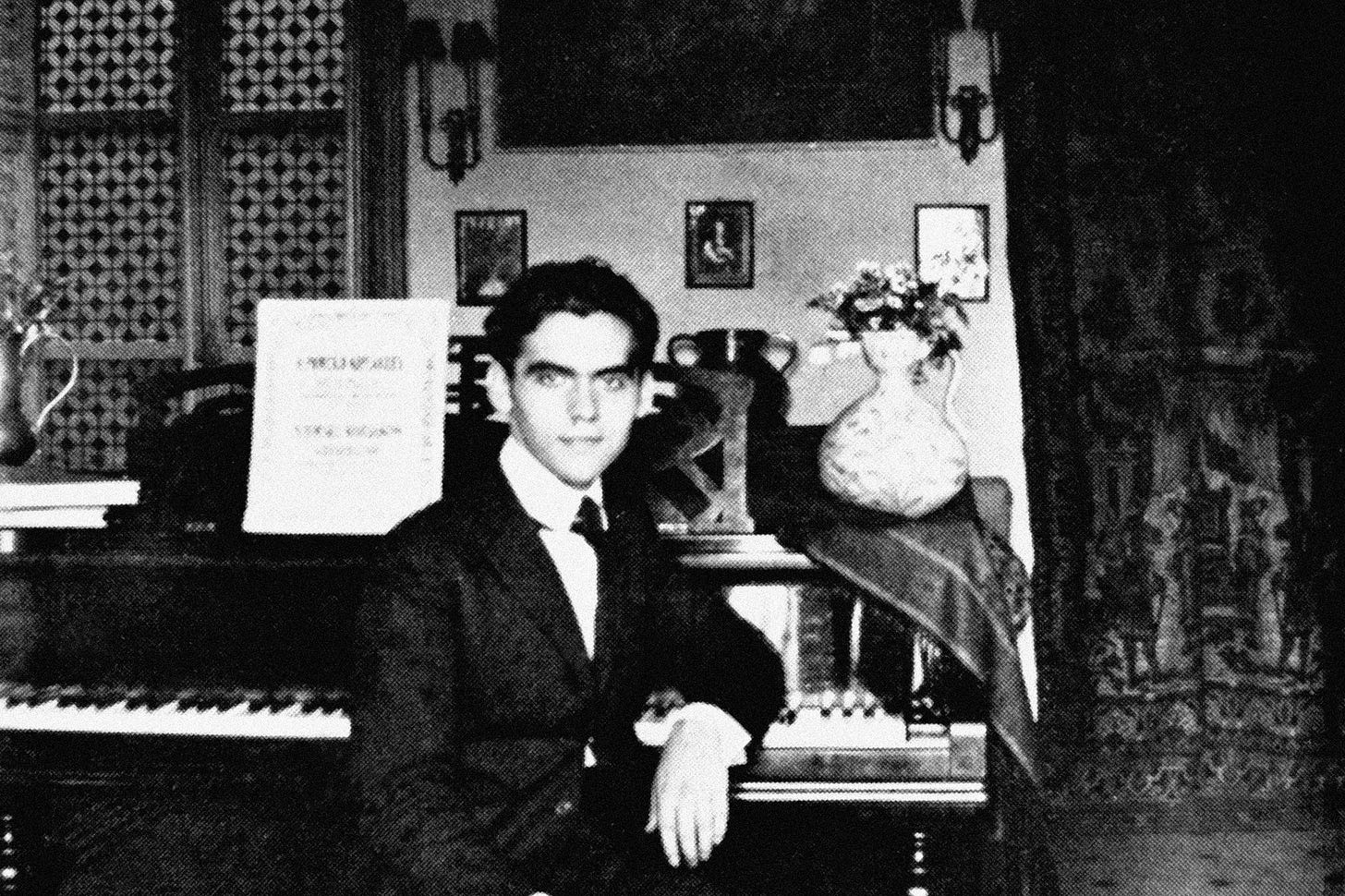

Alone with the bull: The power of Federico García Lorca's 'duende' in art

+ why we love art that makes us feel sad

In a transatlantic radio broadcast in 1935, Spanish poet and playwright Federico Garcia Lorca talked about the mysterious power of the bullring. He believed bullfighting was an ancient art form, a “dark religion” that ensnared the Spanish people as if by siren song, and that its magnetic pull came from “an irrational force which cannot be explained, even by the person who feels it.” He said that “the urge to face the bull claws like a mountain lion at the heart of young boys”, and that when speaking to a young man who wanted to be a torero (bullfighter), the young man said, “I was alone in the fields yesterday, and I suddenly felt so much love that I began to cry”.

For Garcia Lorca, the “irrational force” did not stay within the bullring. Its power existed in all performance art, and its root was ancient and earthy and innate in us all. He believed this force was the “substance of art” and he gave it a name: duende. He said that an artist acted as a conduit for duende, like a “corkscrew that gets art into the sensibility of an audience”. We have all at one time or another experienced duende, even if we didn’t know its name.

Duende is the deep, twisting feeling that you have while watching (or performing) a particularly potent piece of art, it is something that “everyone senses and no philosopher explains”. It is the opposite of intellectual and in fact it abhors anything of the sort, because duende cannot come from the cold rationality of thought – it is purely emotive, it is pure emotion. But duende is not sentimental or gooey; it is dark and it hurts. In an essay called Play and Theory of the Duende, Garcia Lorca quoted his friend and legendary singer of Spanish deep song Manuel Torre, who said: “All that has dark sounds has duende”. If you have ever listened to a song, or saw a film, or watched a live performance, and something about it felt like an arrow in your heart – olé! – that was duende.

Duende is powerful because it is entwined so closely with death. “The duende does not come at all”, said Lorca, “unless he sees that death is possible.” When we experience duende through art, we are forced to reckon with our mortality, and that “ants could eat [us] or that a great arsenic lobster could fall suddenly on [our] head”. We know that one day we will die, and duende brings that painful knowledge to the surface. It reminds us that time is finite and that the sun will set on some love or ambition or tragedy of ours. For each of us, there is something that will never be (never again seeing a loved one who has passed, never returning to the place or the person you had once been, never achieving what it is you once dreamed) and you will die with the pain of it still in your heart. The wound from where that pain emanates is a darkened gate where the duende creeps in and runs barefoot through your soul.

Duende speaks to our most private pain. It doesn’t heal hidden wounds but acknowledges that they’re real, often when you who is carrying them around inside of you will not. It does not promise hope, but instead gives hopelessness meaning. Your pain isn’t pointless when you can hear it in a beautiful song or see it played out in a sad story. Garcia Lorca puts it best when he says that duende can: “baptise in dark water all who look at it, for with duende it is easier to love and understand, and one can be sure of being loved and understood.”

To press down on a wound can give it short term relief, which is one reason why we turn to art and performers for duende. Lorca said: “Each person in the audience fights the bull along with the torero… And thus the torero bears the yearning of thousands of people, and the bull plays the leading role in a collective drama.” At the end of the performance the spectators go home cleansed, for a time, by this ritual of duende. But for Lorca’s weeping torero there is nothing but the bull. He does not perform for applause or money, said Lorca, but because he aches “to be alone with the bull, an animal he both fears and adores, and to whom he has much to say.”

To battle duende is to go toe-to-toe with death, and we can feel at our most alive when straining against our own mortality. When death is close the mundanity of life melts away, and everything becomes wonderfully, terribly vivid. To express pain in such a way is cathartic and exhilarating, and in lieu of other happiness, it is a deeply seductive route to feeling something, anything. But at the expense of potential happiness, it can become an altar that you throw yourself away on – a futile sacrifice to Lorca’s “dark religion”.

I open my eyes and I am in a bullring. I don’t know how I got here, but more and more I fear that I came here on my own. I opened the gate, I think, with my own hands, and perhaps I walked myself to the centre. I stand now, in another world, with the blood red cape unfurling from between my fingers. In my heart I want to be alone with the bull, an animal I both fear and adore, and to whom I have much to say.